Originally published in CNBC

By Florence Comite, M.D.

Quarterly reports soon may take on a new meaning thanks to Mark Cuban.

The billionaire investor sparked a Twitter storm recently, when he tweeted that he thought it was smart to get blood work done regularly — as often as quarterly — and track the numbers, like a stock chart, to make sure no black swans were lurking and nothing nasty was taking a slow turn in the wrong direction.

Innocuous idea, right? Well, some well-meaning journalists and health-care policy wonks called him a twit, a dilettante playing doctor, for not also raising the problems associated with frequent medical testing of almost any type — namely the cost, the time spent by an overstretched physicians and nurses, the false positives and false negatives, the unnecessary biopsies and treatment.

Cuban, at best, was premature, the Twitterati asserted, his prescription years away.

But such naysaying is just, as the kids say, so Twentieth Century.

The speed with which medical research moves today, particularly in the field of diagnostics, bio-hacks and tools for what has become known as precision medicine, is accelerating at a pace similar to the early developments in the computer revolution a generation ago. Just look at the biotech stock boom.

Will there be errors? Medicine will never be foolproof. Will it be expensive? Potentially, although taking a proactive approach to your health can certainly pay off in the end. Should any individual self-test and analyze alone? No way — you need someone with the wisdom to translate your results. Will it provoke unnecessary fears? Most Americans should be more scared when they step on a bathroom scale.

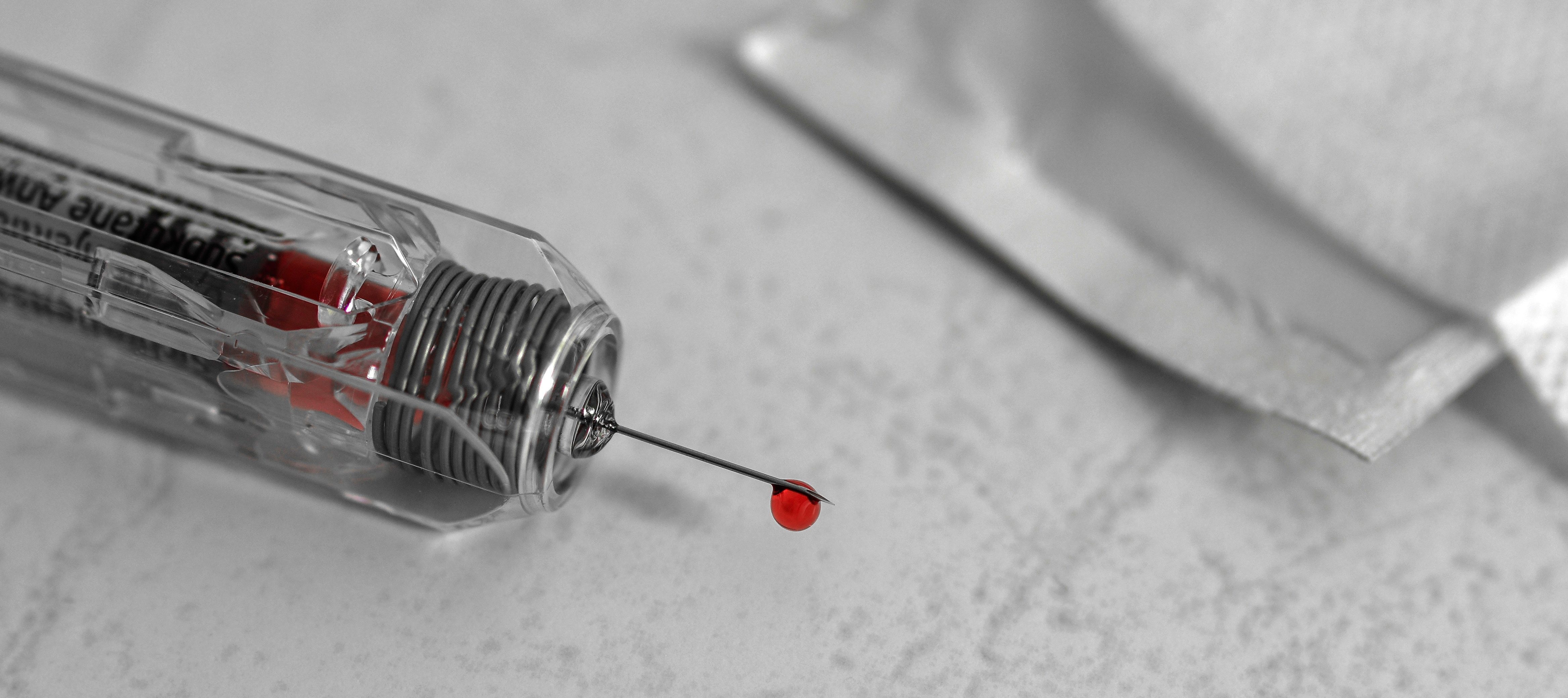

Bottom line: Blood test results are your health resume; they offer snapshots of your health at the molecular level; they identify disease existing in your body; they provide a spectacular early warning system to identify illnesses such as diabetes and coronary artery disease decades prior to symptoms manifesting.

Sure, convention says, let’s wait, come back in six months, we’ll watch it. Watch it? Watch it go from bad to worse? Why wait? Own your health destiny; change your health trajectory.

Yes, some believe, paradoxically, that less medical information leads to better outcomes; “Less is more” is their mantra.

To be fair and precise, more health data may not necessarily be better. It’s the interpretation of the results that matter. And, it requires more than monitoring trends across multiple data points, each in isolation, but rather the strongest analysis comes from understanding the inter-relation between them all. Most doctors are not trained to read massive data sets to draw conclusions from factors that range from the genetics, hormones, blood, diet, history and lifestyle. But with expanding computer power and the cost of sequencing the genome of any individual dropping, this big data-style analysis is the future of health care.

As with any new advance, there are early adopters. In this case, it’s the emergence of people known as self-quantifiers. Mark Cuban is one. Angelina Jolie, who has been keeping close tabs on herself and taking action due to genetic cancer risks, is another.

Another interesting case is an astrophysicist named Larry Smarr. One of the early architects of the Internet, Smarr had been tracking data on his bodily functions in a weight-loss effort, and was able to see the inflammatory markers that made him aware that he had a problem long before he was eventually diagnosed with Crohn’s disease. His physician dismissed the data, and only was able to diagnose him via his eventual symptoms. Smarr, convinced that individualized data monitoring and analysis is the future of health care, is now working on what he imagines will be, in ten years time, a vast distributed computer system that will be able to process a working computational model of millions of individuals’ biomarkers, down to their genetic code.

We already know that when the right data reaches the right analysis, amazing things happen. This is the basis for precision medicine, an emerging field dedicated to the proposition that medicine works better when it is not a one-size-fits-all model, and in which we examine a maximum of data on a single individual.

I would argue that monitoring blood tests and other biomarkers, in particular, along with having knowledge about family history, lifestyle, and genomes, should be at least as important as collecting and monitoring personal financial data.

Would Mark Cuban have been called out if he had said you should check your credit score on a quarterly basis? Isn’t your health more important than your pocketbook? Money cannot necessarily buy you back your good health once it’s lost.

Testing often seems unnecessary — until it isn’t.

And similar to finance, trends are vital, too. In health care, the best time to develop a baseline is when a person is in his or her 20s. That’s their peak. Regular testing will show the slow inevitable decline through the decades. And it will also help demonstrate the efficacy of your efforts to stay healthy.

The right data, at the right time, examined by medical experts who know what they are doing and what to look for, from a proactive and not just a reactive perspective, is never too much data. In fact, it is the future.

I know of no field or endeavor where maintaining an existing level of ignorance is productive.

Commentary by Dr. Florence Comite, an endocrinologist and founder of ComiteMD, a private precision-medicine practice in Manhattan. She is the author of “Keep It Up: The Power of Precision Medicine to Conquer Low T and Revitalize Your Life.” Follow her on Twitter @ComiteMD.